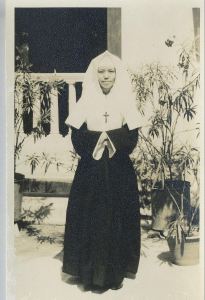

Sister Valerie Tseng, or Aunty Mary will celebrate her 91st birthday this year. It will also mark the 62nd year of her vocation as a nun with the Sisters of the Infant Jesus, a Catholic order founded in France in 1675.

While many of us would be in awe of her life-long commitment to her vocation, it is her achievements within the Order that mark her truly as a woman of substance.

Sister Valerie was born in 1924. She was the third in a large family of eight siblings, and the only girl. Originally named Mary, she was confident, intelligent and outspoken. They were Anglicans but after a few years of attending school at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus, she and her brothers, who attended St Joseph’s Institution decided to convert to Catholicism. She remembers that her brothers egged her on to represent the siblings to get permission from her mum and dad. Her parents were strict, and it took guts to broach such a sensitive topic, but she did it. The parents relented, and they converted shortly after.

Aunty Mary never intended to be a nun. She was a qualified teacher, had a steady boyfriend and the plan was to get married and settle down.

God obviously had other plans for her.

It was 1950. The boyfriend had gone for an extended business trip to India. While he was away, Aunty Mary went with her friend, Margaret, to Kota Kinabalu (it was called Jesselton then) to promote the Legion of Mary in the nearby villages. The mission trip was far from easy. There were no roads, no running water, no proper sanitation. Her mode of transport was on foot via muddy ruts through padi fields and the Mill House Congregation of nuns that worked in the area lived with only the barest of necessities.

It was then that she received the calling to serve.

“Why me, Lord? I have a boyfriend already!” was her initial reaction. Confused, she returned to Singapore and went to her parish priest, Father Meisonniere, for guidance.

Father Meisonniere, however, sent her on her way. “It is not a calling,” he told her. Little did she know that this was actually the padre’s test. The religious life was not for everyone, and it would mean a lifetime of sacrifices for Mary. If the calling was real, it would persist.

True enough, the gentle urging never went away. “No matter how hard I tried to push the voice away, it kept coming back,” she reminisced. She was conflicted and confided in Margaret. “If I were you, I would go see Father again,” urged Margaret. When she went back again to see the priest, he knew that this was the real thing. “When he finally confirmed that this was genuine and I accepted that this would be the path I would take, the urging went away and I felt a great peace,” she said.

The priest then asked her which religious order she planned to join. The Mill House Congregation based in Jesselton was her first choice but at the time, they did not accept local girls, as it was a British order. The Congregation of the Holy Infant Jesus (now known as the Sisters of the Infant Jesus) was the other option that she was familiar with but it was not her preference. She had an unpleasant experience with a few of the Lay Sisters, Europeans who were too “colonial” in mindset. They were kind and friendly to the privileged but were rude and gave no time of day to the poorer students. Father Meisonniere had a different view point. “Pray, don’t imitate the Lay Sisters. Be a good religious and an example for them to follow,” was his advice.

So it was settled. Mary joined the Infant Jesus Sisters and was sent to Penang. After her first year, she took the first formal step with the Pris D’Habit, or the donning of the habit. Wearing the nun’s habit in the fifities was a sacrifice in itself. Made for the cold European climate, the habit was made of serge and and comprised many layers. Aunty Mary remembered quite a few novices passing out from the heat at the Pris D’Habit ceremony – it was just too hot in those clothes!

As a young nun, Mary’s task was to teach Mathematics to the senior middle students in the Ave Maria Convent in Ipoh, a task she initially found daunting as she felt she was not qualified enough to teach Advanced Mathematics. Nevertheless, she soldiered on.

Three years flew by and in 1957, Mary travelled to Paris, France where she received her Final Vows and took on the name of Sister Valerie. Thereafter, she was sent to Liverpool in the United Kingdom to study Advanced Mathematics for a year before returning to Malaya to teach.

The Malaya that Sister Valerie returned to was radically different. It was no longer a British Colony and was now an independent nation. As a holder of a Malayan passport, Sister Valerie taught at the IJ Convent in Pulau Tikus, Penang, for the next 13 years. A capable and strong leader, Sister Valerie was eventually elected Mother Superior in Malaysia.

In 1971, Sister Valerie was sent to attend the General Chapter, a meeting of the IJ Order that took place once every five years to chart the future of the Order and to elect the international leadership team. At the General Chapter, Sister Valerie was one of five Council members elected to assist the Superior General, Mother Maria Del Rosario Brandoly, in leading the Order. This was a significant step as Sister Valerie was the first ever Asian Sister to be elected to the Council. She went on to serve two terms on the Council, each lasting six years.

For the next 12 years, Sister Valerie was based in Rome, Italy, as part of the core group that developed the new constitution for the Order. As part of the Council, she had a hectic schedule and travelled the world, accompanying the Superior General in seeing to the smooth running of the Order. Not unlike a busy CEO, Sister Valerie travelled from Japan to Spain to Bolivia, learning Spanish, Japanese and Italian to better communicate with the people in each market. She did not like Rome much – ‘much too hot in Summer, and dust everywhere!’, but relished her travels, as it opened her to new experiences and viewpoints in engaging with the community and ensuring the growth and renewal of the IJ Order.

When her term was over, Sister Valerie returned to Asia where she was tasked with explaining the recently amended constitution to IJ institutions in the region. Ironically, despite being home, she did not feel entirely welcome. The nuns in Asia were too much in awe of her ‘seniority’, and kept her at arms length. “They sent me to Cameron Highlands when I first returned. I guess they had no idea what to do with me and probably felt a little threatened. It was a bit of a double-edged sword,” she mused.

Over the years, she went wherever she was needed, travelling throughout Asia and moving from Convent to Convent in Malaysia as a teacher.

Today, she lives quietly in Johor Bahru, still helping out with the community. Until recently, she cared for a little girl who was abandoned by parents who were drug addicts. Looking back at her life, she says simply: “This was my path. The Lord had planned it this way. No matter how hard you try, if he calls, you follow, or you will never truly know peace.”